Sea Rise Science

Few places on the planet will be impacted by global warming and the resulting sea level rise as much as South Florida. In fact, some predictions suggest that over the next several decades much of what we know of Miami Dade County and Monroe County today will be gone forever. As Rolling Stone Magazine announced, much of South Florida could become a modern day Atlantis. The impact of sea level rise is already being felt all over South Florida. In Miami Beach, for example, Alton Road and many other streets on South Beach have become routinely flooded in recent years at peak high tides that push sea water into local homes and businesses. |

SIGN UP |

|

The streets themselves become covered with salt water from the ocean and are rendered un-useable. To attempt to reverse the current impacts of sea rise the City of Miami Beach has been at the forefront of taking action through infrastructure improvements to local roads, sidewalks and drains by installing a unique pumping system designed to push the salt water back out to sea; a project whose initial cost is estimated at $450 million dollars. And yet, as crippling as this problem has been to the community of Miami Beach and our region, they have only begun to feel the very initial stages of the devastation and destruction that is likely to come in the decades ahead. And to be clear, the threat of sea level rise threatens far more than the edge of our coast or its barrier islands. At risk is trillions of dollars of existing infrastructure, buildings, and improvements that in some cases have existed for a century or more. Also at risk are human habitat, people’s lifestyles, tax revenue and industries such as tourism and agriculture, as well as countless animals and the habitats in which they live in. And because of the porous nature of South Florida’s geology, the threat of sea level rise is not only confined to those areas on or near the water, but those that are inland as well. As the seas rise, so too will the water under our state, up and through our porous limestone and into lands all the way to, and even through, the Everglades to our west. Few places on the planet are more at risk to the threat of sea level rise than South Florida, and it is for that reason that the Sink or Swim project exists, including this website that you are looking at today. Because of the risks that our region faces, local governments and leaders have been forced to begin analyzing the problem at a time when much of the country is unaware of what lies ahead and when politics, or entire industries, attempt to make solving the issue challenging. If you want to learn about sea level rise here in South Florida, chances are good that you’ll find what you’re looking for here. From government planning documents that outline the threat that sea level rise presents to our communities, as well as possible solutions, to articles of interest and other materials on the topic, it’s here to help you learn and to become engaged. Most of the scientific data, graphs, charts, and commentary, are from the 2013 and 2014 IPCC Climate Change Work Groups I and II as published by Cambridge Press. These books are nearly 5,000 pages long and summarize the incredibly important work by tens of thousands of scientists, authors, contributing authors, and editors from around the world. Other sources of data include the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Environmental Protection, NASA, as well as interviews conducted with local, scientific thought leaders and their research. |

|

Our Warming Planet

CO2 & Greenhouse Gas Growth in our Atmosphere

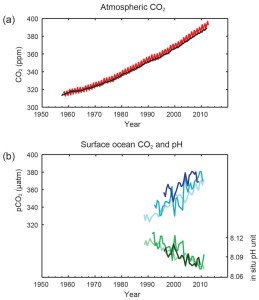

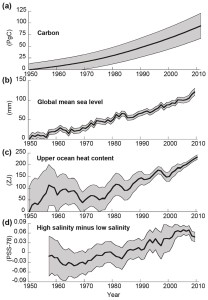

More Carbon (CO2) In Our Atmosphere & OceansThe first (a) chart here illustrates the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere from data at two locations on earth (Mauna Loa, in red, and the South Pole, in black) since 1958 and the ongoing trend in both locations is obvious. The second chart (b) illustrates how the surface of the ocean’s CO2 content has changed since the late 1980’s when it was first measured (its increased) as well as how the pH (acidity) has changed. pH is a scale that measures acidity in our oceans that, according to the EPA, ranges from 0 to 14. A pH of 7 is neutral, a pH of less than 7 is acidic, and a pH of greater than 7 is basic. A decrease in pH results in our oceans illustrates an increase in acidity which is a threat that, over time will impact our coral reefs (bleaching and killing them), oceans, food supplies and thus planet. Multiple observed indicators of a changing global carbon cycle: (a) atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) from Mauna Loa (19°32’N, 155°34’W – red) and South Pole (89°59’S, 24°48’W – black) since 1958; (b) partial pressure of dissolved CO2 at the ocean surface (blue curves) and in situ pH (green curves), a measure of the acidity of ocean water. Measurements are from three stations from the Atlantic (29°10’N, 15°30’W – dark blue/dark green; 31°40’N, 64°10’W – blue/green) and the Pacific Oceans (22°45’N, 158°00’W − light blue/light green). Source: CLIMATE CHANGE 2013: THE PHYSICAL SCIENCE BASICS, Working Group I Contribution To The Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, 2014 |

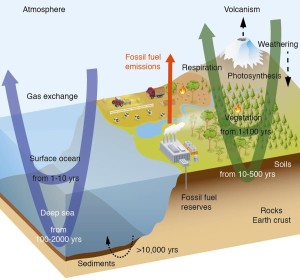

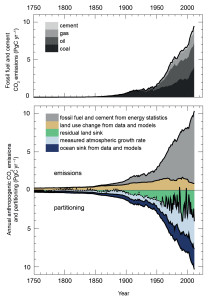

Industrialization Leads To Clear Growth In CO2 Production From Fossil Fuels (Gas, Oil & Coal) And Cement ProductionJoni Mitchel explained to writer Alan McDougall that she wrote her song ‘Big Yellow Taxi’ on ‘my first trip to Hawaii. I took a taxi to the hotel and when I woke up the next morning, I threw back the curtains and saw these beautiful green mountains in the distance. Then, I looked down and there was a parking lot as far as the eye could see, and it broke my heart… this blight on paradise. That’s when I sat down and wrote the song’. This chart is fascinating in that it depicts the CO2 produced from fossil fuels and the production of cement of time dating from 1750 to 2011. As you can see, for the first 100 years the amount of CO2 from fossil fuels and cement production is non-existent. However with the start of the first and then second Industrial Revolutions, including the introduction of fossil fueled transportation (trains, ships, cars, trucks and planes) and global construction booms (all of which utilize cement) the volume of CO2 has grown by and to alarming levels. The second chart illustrates the growth of CO2 from Fossil Fuels and Cement Production along with reduced land (called land sink and attributed to deforestation across the globe) as well as the volume of our ocean polluted by CO2 and thus reduced in quality (called ocean sink). Annual anthropogenic CO2 emissions and their partitioning among the atmosphere, land and ocean (PgC yr–1) from 1750 to 2011. (Top) Fossil fuel and cement CO2 emissions by category, estimated by the Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center (CDIAC). (Bottom) Fossil fuel and cement CO2 emissions as above. CO2 emissions from net land use change, mainly deforestation, are based on land cover change data. The atmospheric CO2 growth rate prior to 1959 is based on a spline fit to ice core observations and a synthesis of atmospheric measurements from 1959. The fit to ice core observations does not capture the large inter-annual variability in atmospheric CO2 and is represented with a dashed line. The ocean CO2 sink is from a combination of models and observations. The residual land sink (term in green in the figure) is computed from the residual of the other terms. The emissions and their partitioning include only the fluxes that have changed since 1750, and not the natural CO2 fluxes (e.g., atmospheric CO2 uptake from weathering, outgassing of CO2 from lakes and rivers and outgassing of CO2 by the ocean from carbon delivered by rivers) between the atmosphere, land and ocean reservoirs that existed before that time and still exist today. Source: CLIMATE CHANGE 2013: THE PHYSICAL SCIENCE BASICS, Working Group I Contribution To The Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, 2014 |

Sea Level Rise

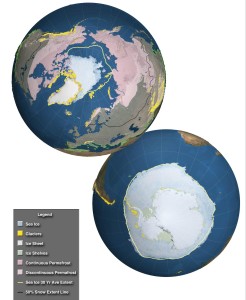

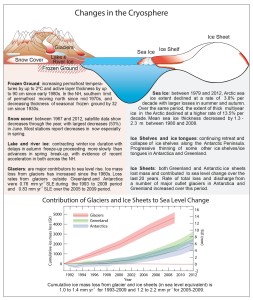

Glaciers & Icebergs: Our Melting Cyrosphere

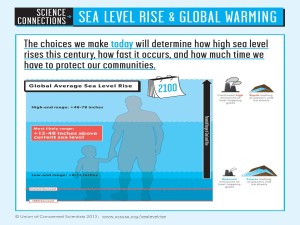

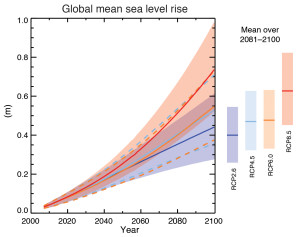

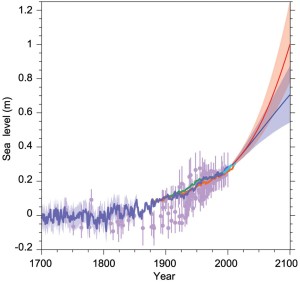

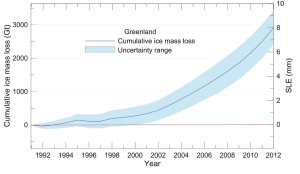

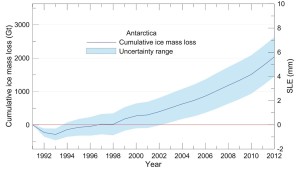

Global Sea Level RiseIf you’ve ever seen a chart on sea level rise and predictions for the future chances are it is this one. The volume of science, much less the thousands of scientific writers and reviewers, that supports the IPCC projections that you see here is truly significant. By design the projections that the IPCC, United Nations and associated Countries typically discuss are on the conservative side of the estimates that are illustrated here, in the range of ,03 meters to about 2 meters (approximately 6 feet). It is, however, very possible that the higher range estimates, six meters (about 18 feet above today’s levels) to 8 meters (about 24 feet or so) could take place nearer the end of this century especially if the Greenland ice sheet melting accelerates as some models predict will take place. Projections of global mean sea level rise over the 21st century relative to 1986–2005 from the combination of the CMIP5 ensemble with process-based models, for RCP2.6 and RCP8.5. The assessed likely range is shown as a shaded band. The assessed likely ranges for the mean over the period 2081–2100 for all RCP scenarios are given as colored vertical bars, with the corresponding median value given as a horizontal line.

Source: CLIMATE CHANGE 2013: THE PHYSICAL SCIENCE BASICS, Working Group I Contribution To The Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, 2014 |

SOUTH FLORIDA MAPS: Sea Level Rise Projections

|

|

|

| 15 years & seven inches | 45 years & 24 inches | 85 years & 36 inches |