A Coastal Catastrophe

Although the year is only slightly more than half over many of my colleagues in the scientific community are already predicting that there’s a good chance that 2023 may become the hottest year in Earth’s history. Record breaking high temperatures and the duration of that heat has rightfully alarmed people, while also damaging environments all over the planet. And nowhere should those alarms be louder than right here in Florida where we are amidst what could very well be a coastal catastrophe caused by that heat. Heat, I dare say, that is largely fueled by man-kind’s use of fossil fuels.

Miami, where I principally live, experienced over three weeks in a row of Excessive Heat Warnings from the National Weather Service last month (July 2023). The prior record for such warnings were three days. In fact, for 46 scorching hot days (June 11 to July 27) this summer, Miami sizzled under heat index temperatures that topped 100 degrees every afternoon. That broke the prior record (from 2020) of 32 days in a row above 100 degrees. A heavy rainstorm on July 28th ended the streak by producing a downright cool 98-degree day. During those 46 days Miami set 10 daily temperature records, 27 daily heat index records, received its first-ever excessive heat warnings from the National Weather Service, and was subject to 23 days of heat advisories. What did the rest of the planet do during that time frame this summer? Well, it set a new all-time temperature record and then broke it three times.

“This isn’t just Miami in July heat. Miami isn’t just breaking its record heat index values — we’re absolutely obliterating the previous records on a daily basis. Miami is well on its way to recording the hottest year meteorologists have seen in 130 years of keeping weather records. Thanks to climate change, this summer is likely a preview of summers to come.”

NBC 6 Hurricane Specialist, Meteorologist, John Morales

My friend and fellow CLEO Institute Board Member, NBC 6 Hurricane Specialist John Morales, was widely quoted in recent days as explaining, “This isn’t just Miami in July heat. Miami isn’t just breaking its record heat index values — we’re absolutely obliterating the previous records on a daily basis.” John went on to say that “Miami is well on its way to recording the hottest year meteorologists have seen in 130 years of keeping weather records. Thanks to climate change, this summer is likely a preview of summers to come. This summer should repeat with much greater ease here in South Florida because of the trend of hotter temperatures all around the planet, which is undeniable, and undeniably linked to mankind and our continued burning of fossil fuels”. John, I could not agree (nor thank you for your sensible analysis) more.

As I write this post I am home here on No Name Key in the Florida Keys after a summer of travel to many of America’s iconic western National Parks (you can read a bit about that trip here). Florida, where I live, is a peninsula with 1,350 miles of mainland coastline abutting the Atlantic ocean to our east and the Gulf of Mexico to the west with the waters of Florida Bay to the South. The Florida Keys is a magical chain of about 1,700 islands running from the southern “tip” of Florida’s mainland where Miami, Naples, and the Everglades National Park are located to the west through the Gulf and Ocean waters before culminating in the Dry Tortugas National Park. Needless to say, most of mainland Florida and all of the Florida Keys are surrounded by water and it’s in those coastal waters that the catastrophe I write about today is brewing.

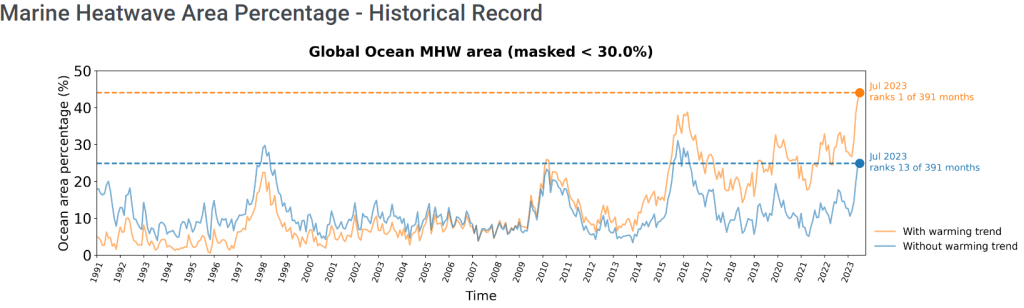

In its July 2023 Marine Heatwave (MHW) discussion post, the National Oceanographic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) concluded that in 2023 44% of the global ocean is experiencing a Marine Heatwave. That percentage, 44%, ranks first since such conditions began being measured in 1991. NOAA expects that this figure will grow in the months ahead and that approximately 50% of Earth’s oceans will experience a Marine Heat Wave in September-October of this year. Here’s the MHW data from 1991 when records were first kept through last month (notice that as time passes the temperatures have increased?):

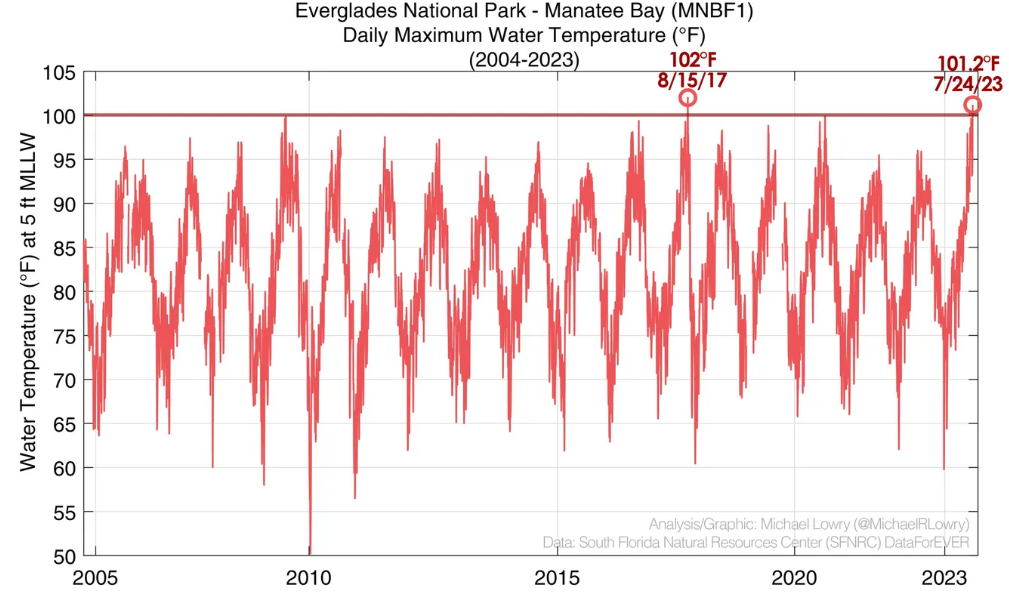

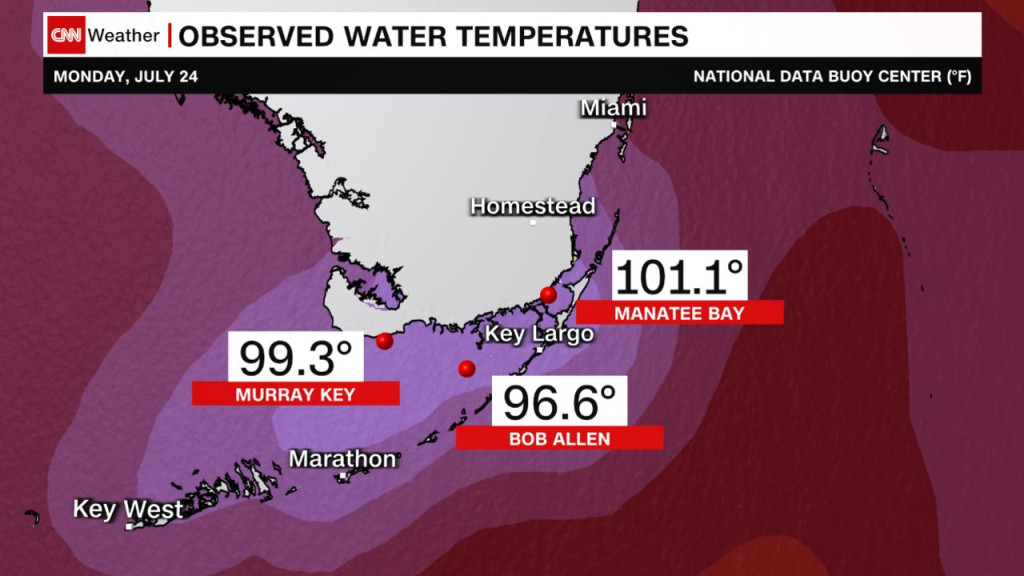

Now closer to home, consider Manatee Bay, a shallow basin just off the southern tip of mainland Florida near Everglades National Park, where a temperature of 100.2 degrees was recorded one night last week only to be followed by a temperature of 101.2 degrees the very next day. In 2010 the temperature there hit triple digits (100 degrees) for the first time and then in 2017 set a record at 102 degrees so last week’s 101.2 reading appears to continue a trend that portrays triple digit temperatures taking place more often. Here are the historic water temperatures from 2004 through last week, 2023 in Manatee Bay.

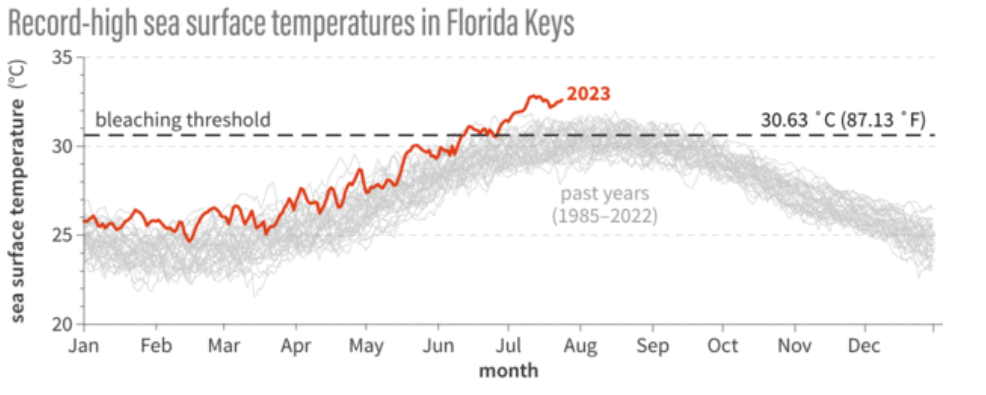

But it’s not just Manatee Bay that’s boiling. It’s all the waters around South Florida including the Florida Keys. According to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) typical water temperatures for the region this time of year should be between 73 degrees and 88 degrees (23 and 31 degrees Celsius), yet they have been averaging about 91 degrees (33 Celsius) in recent weeks, thus much higher than the normal mid-July average of 85 degrees. NOAA and its partner Coral Reef Watch have prepared this excellent graph which displays that sea surface temperatures in the Florida Keys have been well above average for much of 2023:

And it’s not just in Florida that sea temperatures have increased, but this is happening all over the world. Travel up the eastern coast, for example, to Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, places I visited in 2019 as part of a geology expedition, and you will find sea temperatures that are 9 to 11 degrees hotter than is historically normal. One or two degrees would be alarming but 9, 10, 11 degrees portrays a catastrophe. Perhaps of even greater concern is that the worst might be ahead of us in August or September when water temperatures typically peak. In fact, NOAA’s experimental Ocean Heat Wave Forecast tool that I shared earlier in this post now suggests that there is a 70-100% chance that the extreme heat in the North Atlantic will continue through September or even October. And, as noted above, NOAA believes that 50% of Earth’s oceans will experience a Marine Heat Wave in September / October of this year.

So what’s the big deal with a warmer ocean? Well, aside from the dire impact warmer water has by increasing the melting rate of glaciers which, in turn, causes seas to rise, such temperatures also harm animals within the water and can damage or destroy habitats forever. Warmer water houses less oxygen and that can lead to mass fish kills. It can also kill sea grass, especially in shallow beds such as those that are prevalent here in the Florida Keys, that many species rely upon for food and shelter. And warmer water can help algae grow more quickly which, in turn, can lead to algal blooms that cause added environmental damage.

And speaking of the threat to animals, coral for example, is a living, breathing organism that is vital to our marine environment, protecting the mainland, and to our economy. Florida’s coral reefs annually produce billions of dollars in economic benefit from tourism and fishing. They are a vital natural buffer from hurricanes. They are also, of course, habitat for countless marine life on which our ecosystem depends. They are, in short, a critical natural resource and yet, like so much of our natural environment, they are at dire risk of extinction because of mankind’s love affair with fossil fuels and the resulting warming temperatures from those fuel emissions pouring into our atmosphere and oceans.

You see, algae lives (or tries to, temperature permitting) inside the coral and provides coral its color and food. Coral is, however, highly susceptible to higher temperatures which, when present, can lead to what is called bleaching, which is what happens when coral expels the algae due to higher temperatures than the coral can tolerate. It’s a bit like throwing a blanket off yourself in the middle of a warm summer night’s sleep to try and cool down. When coral expels its algae to cool itself, it’s also throwing its food away and, thus, can starve.

Depending on the amount of heat and its duration, some corals can recover from brief bleaching events but as waters increasingly warm and last longer these events can kill the coral. The stark white coral in the picture above and the one below are examples of what bleached coral looks like.

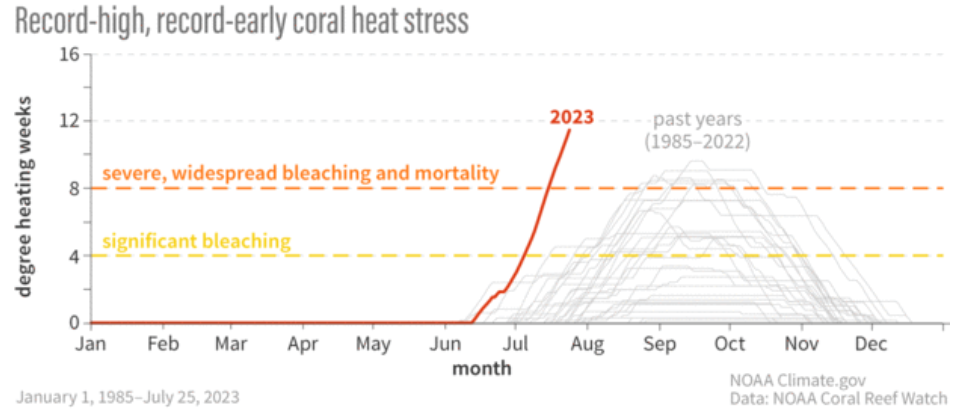

Up until about 40 years ago bleaching was rarely observed but as our water temperatures have continued to rise from climate change it has become more and more prevalent in recent decades. Certainly what we are seeing this year, both in the temperature and how early bleaching is taking place, is the earliest since satellite records began being used in 1985. Perhaps worse yet is that the warmer waters we would normally expect in August or September appear to be arriving earlier and earlier each year. Higher temperatures combined with longer durations of those higher temperatures are catastrophic for coral. The chart below, also from NOAA / Coral Reef Watch, illustrates stress on coral based both on record high temperatures and setting a record for how early the warming took place.

And what do I see here in the waters off No Name? A lot of dead and dying coral struggling for survival. And snorkeling in the shallow waters around the island in recent weeks is akin to stepping into a hot tub.

“What we found was unimaginable – 100% coral mortality.”

Sadly, others in the region are sharing similarly grave news.

Consider Sombrero Reef, off of Marathon Key just to my east above the Seven Mile Bridge, where the folks from the Coral Restoration Foundation visited their decade old coral restoration site last week and reported the following: “What we found was unimaginable – 100% coral mortality.” Or consider their coral nursery at Looe Key here in the Lower Keys, a favorite dive spot of mine over the years that’s just a short boat ride from No Name, where the Foundation sadly now reports “We have also lost almost all the corals.”

The news, what with warming oceans and warming lasting longer and longer, is not (to say the least) good. That said, and as dire as this situation is, allow me to end with some positive news… at least as positive as is possible given the threat our coral reefs are facing.

First, if our society will only ever take these threats seriously and quickly transition from using fossil fuels to alternative energy sources, we can very likely overcome the current threat to coral from increased temperatures. But we need to act quickly and demand that our political “leaders” set aside the polluting politics of the past and demand change right NOW. If you are worried about what’s happening and want to play a role in fixing the problem please contact your state and federal representatives and demand action by eliminating fossil fuel use.

Secondly, I am deeply proud to report that scientists, environmentalists, and many other concerned citizens have sprung into action (and into the water) in recent weeks to save as much juvenile coral as possible by moving it into climate-controlled labs or into deeper, cooler water. As rising temperatures threaten our coral populations, a variety of amazing stakeholders including our government, universities, and non-profits have been growing new coral and planting them all along our coast to attempt to replenish dead and dying coral. To save that coral, countless folks are in the water right now trying to protect those “babies” by working literally around the clock as I type these words, as well as working to find ways to temporarily protect as many established reef sites as possible.

If we are to ever save our incredible coral reefs here in South Florida, we will most certainly have science and scientists to thank, so please join me with a HUGE Shout Out to everyone who is in the water and their labs right now trying to avert this brewing coastal catastrophe.