I hope you don’t mind my taking a personal privilege with today’s post but I wanted to honor a great man, a true leader, and an agent of change who died on Saturday. Howard Schnellenberger was well known as a successful football coach and you can learn about his professional work in a wonderful article in today’s Miami Herald found here: Legendary coach Howard Schnellenberger, who started the Miami Hurricanes dynasty, dies.

I learned about Coach Schnellenberger or, as he insisted I call him, “Coach” while watching an ESPN documentary about the University of Miami’s historical football program’s successes and challenges and through that piece became intrigued about the social impact that he had on our city and country at a particularly volatile time. And, so, when my 10th grade high school history professor, Dr. Lane, assigned our class a research paper on an American history topic of our choosing, I used that assignment as an opportunity to learn more about the history of race relations in America and to consider what a football coach at the University I was already dreaming of attending could possibly have done to help make things better in some small way.

While Dr. Lane likely expected a paper on traditional topics such as the founding of our nation, the Civil War, or the Salem witch trials (which for some reason was a popular choice for many that year), I thought it would be interesting to speak to someone who was still alive, had made history, and had a tremendous impact on our community. And with that in mind, I set out to find a way to speak with Coach Schnellenberger and was actually able to arrange what I assumed would be a brief call. To my surprise, Coach, in his deep voice that he was so well known for, insisted that we take as much time as possible and promised that he would be happy to answer any and all of my questions. We ended up spending nearly two hours together on the phone that day. He was gracious, deeply insightful, and ever so proud of the important impact that he had off of the football field just as much, if not more so, as on it.

I’ve thought about my conversation with Coach, and the paper I wrote so many years ago, a lot over the past few years amidst the pain that so many in our country are suffering as they rightfully are still fighting for social justice and equality. It amazes but also saddens me that we can live in such an enlightened society, one that has come so far since its founding, but yet has so far to go to achieve the equality that every person deserves no matter what they look like, where they come from, the language they speak, how they identify, or the political views they hold. If the last few years have proved nothing else, they certainly prove that our nation is still a work in progress and that we need a lot more people like Coach to move it forward to be and become “one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all“.

In the event that you read the comments that follow, please keep in mind that they are the words and research at the time of a fifteen-year-old who was still learning about these incredibly important and complex topics. Today, even at 21, the years since I’ve written this paper have illustrated how much so many of us, myself most certainly included, have to learn to make our community and country a better, more just place. Frankly, I am not qualified to fully understand the misery and frustration far too many people have and continue to experience, but what I can understand is that we as a society have a long way to go to reach equality.

Coach, thank you for having a profound and lasting impact. As I wrote at the end of my paper, “The unity that Coach Schnellenberger bestowed on our community and country was easily his most important “national” championship.”

Delaney Reynolds

History Period D

4/22/15

Research Paper

The Scholarship Man

Modern Miami, Florida is considered to be one of the most cosmopolitan, multicultural cities in the world. Our region’s races and cultures range from North American and Native American to European, Asian to Hispanic and African to everything, and everyone, in between. While we are far from perfect, residents within our region today are, for the most part, treated as an equals. But that was not always the case and the price for today’s evolved equality has often come at a steep price. Desegregation of our Country was first introduced during the many United States wars in the 17th century, when armies allowed African Americans to fight in the wars, and had expanded into the United States primary and secondary school system starting in 1971 including elementary, middle, high schools and college. Despite its own, often ugly diversity evolution, one Miami school, The University of Miami, began to break down color barricades earlier than most by desegregating in 1961. However, it was not until two decades later that a football coach at the school built his program in a manner that helped calm a community engulfed in a racial fire and, along the way, played a role in progressing an often racially confused nation. Howard Schnellenberger began coaching the University of Miami’s football team in 1979 and took that job at a time when his school and our community faced daunting challenges including riots that burnt the city for days within a year of his joining the team. While Schnellenberger wasn’t the first coach to ever put African Americans on a college team, the manner in which he built his team during a particularly volatile time in Miami’s history, had a dramatic impact in easing tensions and improving race relations throughout South Florida and changing our community in many lasting ways.

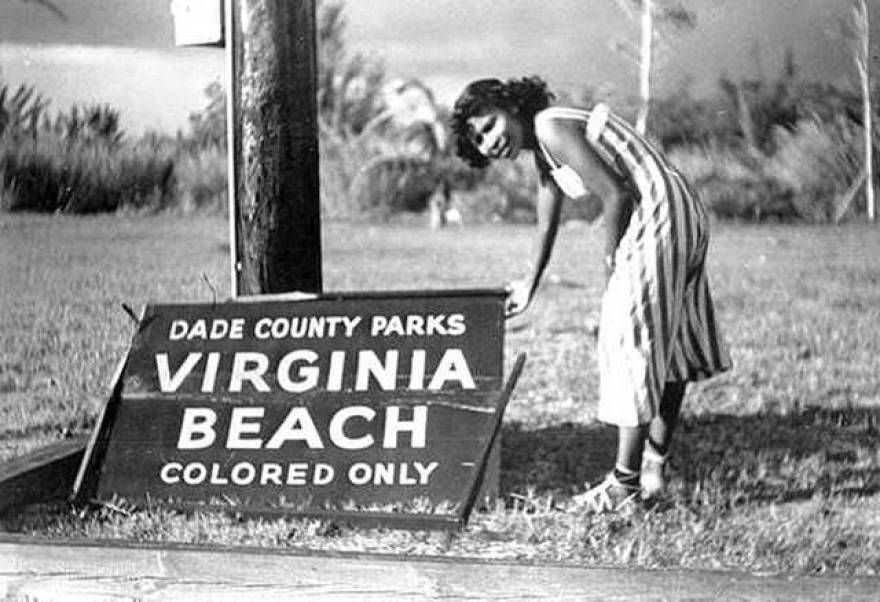

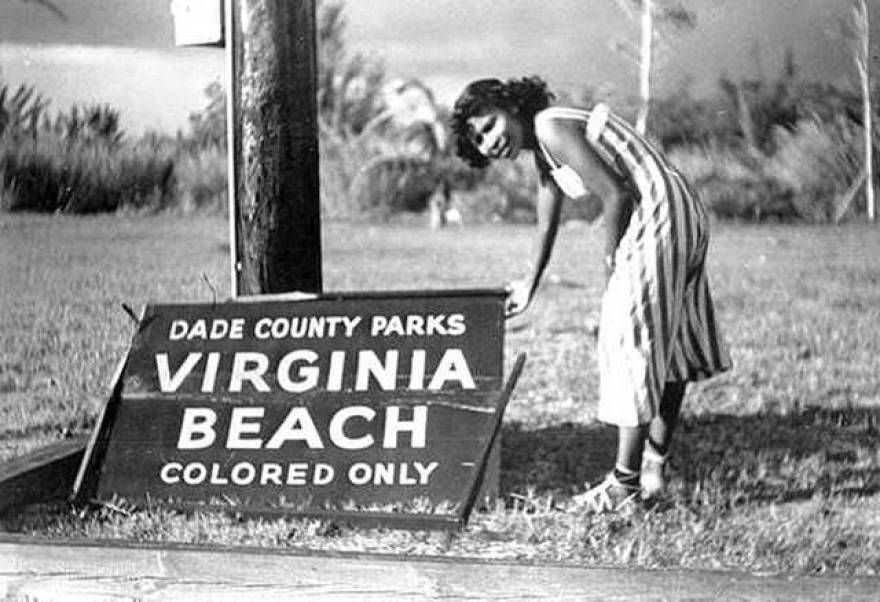

Colored only beach on Virginia Key, Florida

Karales, James. Segregated Virginia Beach. N.d. N.p.

Since the end of the days of slavery, segregation was a way of life in the United States despite many efforts by lawmakers to change the views of the American people. With the abolishment of slavery in the South, African Americans were left to find their place among our predominantly white society and, as a result, American race relations were often strained, uncomfortable, and even violent. Black people were not welcomed into neighborhoods, parks, restaurants, or other places of business simply because of the color of their skin and the stigmas and ignorance associated with race often led white people to believe others were not entitled to equal treatment.

Segregation was a cruel stage for America’s evolving race relations, yet some brave people of color were proudly keen on seeking and exerting their rights despite the tremendous challenges that people’s prejudice subjected them to everywhere they turned. Rosa Parks, a 42 year old African American woman who refused to give up her seat in the middle of a bus one day in 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama, is one such proud American patriot who fought at the dawn of the civil rights movement. Seats in the front and middle of those buses were reserved for white people, and if there wasn’t enough room for them, African Americans were forced to give up their seats to whites and then either sit in the back of the bus or stand during the ride. Parks bravely “sat near the middle of the bus, just behind the 10 seats reserved for whites. Soon all of the seats in the bus were filled. When a white man entered the bus, the driver (following the standard practice of segregation in place at the time in his community) insisted that all four blacks sitting just behind the white section give up their seats so that the man could sit there. Mrs. Parks, who was an active member of the local NAACP, quietly refused to give up her seat” (“Rosa Parks Bus – The Story Behind the Bus”). The civil rights movement began in earnest following the Rosa Parks bus ride that day in Montgomery. Five years later, in 1960, four young black men visited the luncheon counter at the local Woolworth’s Five & Dime Store in Greensboro, North Carolina to enjoy lunch together at its diner’s counter and made history by simply ordering lunch. Sitting down on stools that had, until that moment, been occupied exclusively by white customers, the four men asked to be served lunch, but when they were refused based on the color of their skin they did not get up and leave. Indeed, the men who today are known as the ‘Greensboro Four’ helped launch a protest that lasted six months and helped change race relations in America forever. It is said that “what the students were confronting was not the law, but rather a cultural system that defined racial relations” (Edwards, “Woolworth’s Lunch Counter”).

Despite their push for equality, American blacks remained disenfranchised through the 1960s and 1970s. This was especially the case in the American South where whites often continued to embrace and enforce segregation. The white supremacist group, known as the Ku Klux Klan, was especially active in certain sectors of the South and frequently played on people’s fears through a range of violent acts against blacks including bombing buildings, setting crosses on fire, and even murdering men over the color of their skin. Even the passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, which banned segregation in public places, only provided the Klan heightened determination. When the Civil Rights Movement arose in the Deep South in the 1960s, “the Klan was there to meet it. Its members enjoyed what initially amounted to general immunity from arrest, prosecution and conviction. Many police officers were members” (Chalmers, “Ku Klux Klan”). The terrible reality of the time was that even the most extreme of their enemies, the Klan, was basically above the law and its members were not punished in return for their violence towards the blacks, as many Klan members were insulated by the local police charged to seemingly protect all citizens.

Walk of Selma, Alabama

Walk of Selma, Alabama

Martin, Spider. Selma to Montgomery March. 1965. The Levine Museum, Charlotte, North Carolina

The Civil Rights Movement remains young in America, so much so that one of its most important milestones took place just 50 years ago this year on a bridge in Selma, Alabama. That day in March 1965, today known as ‘Bloody Sunday’, marks one of the most significant and violent attacks on black Americans in the history of our great country. Under the leadership of Martin Luther King, Jr., 600 people walked peacefully across the Edmund Pettis Bridge from Selma towards Montgomery to promote civil rights and equality. The group was, however met by Alabama state troopers with nightsticks, whips, and tear gas, with many being injured, and blocked from crossing the bridge. When one considers that the Selma march was a non-violent attempt to simply raise awareness of the efforts to allow blacks the ability to register to vote in the South, this level of violence seems as outlandish today as it must have in 1965. The good news is that the blood that was spilled that Sunday afternoon in Selma, the pain that was inflicted on those black Americans on the bridge and, by extension, all over America, did not go unnoticed. “The historic march, and King’s participation in it, greatly helped raise awareness of the difficulty faced by black voters in the South” (“Selma to Montgomery March”). Slowly progress was being made as lawmakers worked to help black Americans obtain some improved rights and liberties, yet perceptions, stigmas, and racial tensions continued.

Meanwhile, at the University of Miami, progress was being made, as well. Following less than progressive decisions to not play UCLA in 1940 and Penn State in 1946 because they had black players on their teams, the University evolved into a leader of civil rights. In 1961, the school’s Board of Trustees voted to admit qualified students without regard to race and for the first time ever black students were allowed to attend school on the Coral Gables Campus. In 1962, the first black student to attend the University of Miami, Benny O’Berry, was enrolled in class and in 1966, Ray Bellamy became the first black football player for the University, making it the first major college in the South with a black player on scholarship (University of Miami Department of Diversity Timeline).

White and Black Segregated Water Fountains

Erwitt, Elliott. Segregated Water Fountains. 1950. North Carolina.

Despite the progress being made on the University’s tiny campus the City of Miami and Miami-Dade County were not immune from the nation’s racial tension of the times and those tensions in our community grew greatly in the years that followed Selma. Miami had always had a substantial African-American population, yet blacks continued to be widely segregated in most public facilities, neighborhoods, parks and beaches. The elimination of the laws and customs that restricted blacks from these public places, or desegregation, did not begin until 1954, when the Supreme Court case of Brown vs. The School Board of Education of Topeka attacked the notion of “separate but equal” and banned segregated public schools.

Colored School

Foster, Charles. Milwaukee Springs. 1940. N.p.

Although, legally, freedoms were granted, this ruling was the catalyst to a period of continued prejudice, organized boycotts, student protests and mass marches that went on for years all over America including here in South Florida. Born in Miami in 1963, my own father vividly remembers segregated beaches on Key Biscayne, blacks being relegated to ‘their’ own beach on Virginia Key, next to a County trash dump. My father also experienced Miami’s early efforts to desegregate its schools during the 1970s when he was bused to school from the entirely white City of Coral Gables into the entirely black Southern Coconut Grove to attend Carver Middle School. His stories of daily fist-fights and rampant racial strife are chilling, especially when one considers that these experiences took place less than 40 years ago and at, what is today, a highly regarded ‘Magnet’ School (Reynolds, 15 March 2015).

Howard Schnellenberger arrived in Miami in 1971 as an assistant coach with the city’s young professional football franchise, the Miami Dolphins, and one could have initially assumed him an unlikely civil rights champion. Schnellenberger, who was born into a German household in Indiana, spoke German until the age of 3 when his family moved to Louisville, Kentucky. He went to Catholic schools all of his life until he attended the University of Kentucky and played for Coach Paul Bryant. Perhaps not coincidentally, after graduation Schnellenberger followed Coach Bryant into the Deep South where he became the University of Alabama’s Offensive Coordinator under the man who famously came to be known as ‘Bear’ Bryant and, thus, was not far from Selma and the epicenter of the civil rights movement. When he became Head Coach at the University of Miami, Schnellenberger could not have known the impact he was about to simultaneously have on the school, our community, and the nation (Schnellenberger, 13 April 2015).

By the late 1970s and early 1980s Miami had not only begun to become a true melting pot of cultures, but one that was on the verge of exploding. 1980 was an especially important, volatile year, as the City was flooded with 125,000 refugees who fled Castro’s Cuba, often by raft at the risk of their lives to seek America’s political freedoms. To add to the stress within our community between 1977 and 1980, more than 60,000 Haitians fled to Miami to escape the brutal reign of Jean-Claude ‘Baby Doc’ Duvalier. Long time black, Native American, and white residents began to feel disenfranchised and often uncomfortable with the quickly evolving and expanding ethnic communities. The shift of races and cultures was quick and staggering. In 1950 Hispanics accounted for just 4% of Miami’s population, but by the end of the 1980s 50% of our population was Latino, 30% were white and just 19.5% were black. That “shift” in just a few decades caused all sorts of friction and fear (Portes 172).

By 1980 tensions were already on edge awaiting a “spark” when one incident in May set Miami ablaze with violence and proved how very real racial divisions in our community and country were at the time. A black man by the name of Arthur McDuffie was fatally beaten by four white police officers following a chase. McDuffie, a former Marine and a successful insurance executive, had been fatally beaten while handcuffed after a police chase by a group of white police officers, who then tried to cover the incident up as a traffic accident. After an all-white jury rendered an acquittal of all four officers the black communities of Liberty City, the Black Grove, Overtown, and Brownsville exploded into the streets and went on a rampage of fury and grief. The riot lasted three days, escalating with frightening speed and killing 18 people, costing 3,000 jobs and causing $200 million in damage. After the trial ended Eula McDuffie, Arthur’s mother, was quoted as saying, “My child is dead, they beat him to death like a dog” (The Museum of Broadcast Communications – Encyclopedia of Television – Racism, Ethnicity and Television).

Coach Schnellenberger had always seen the University and the community as being linked together, what was good, or bad, for one had the same impact on the other. Schnellenberger explained by saying, “The city and the university had the same last name. What was good for the U would be good for the community, and what was good for the community would be good for the U. So we got more involved” (Schnellenberger 117). Unlike his predecessors before him, the school’s new coach embraced the entire City and decided to attempt to build a “wall” around it to keep its best players home to play in college in the city they grew up in, as well as to build a fan base of local residents. Schnellenberger immediately began to recruit all over Miami and spent a great deal of time in traditionally black neighborhoods such as Liberty City, Brownsville, and Overtown. When I asked him how he was viewed as a white man driving into in these entirely black, impoverished neighborhoods at a time of horrific violence and racial tension he explained with a laugh, “I was received very well because the people got to know that I was there to give their good football players an opportunity for a free education to go on scholarship. When I would go into Liberty City and Overtown, I would drive in there with my white Cadillac, with the ushers on bicycle, with the grade schoolers riding next to me on their bicycles, they would see me coming in and they would send the word out and as I passed people’s houses, they would come out and say ‘the scholarship man is coming, the scholarship man is coming,’ and they would follow me up to Melvin Braton’s or Alonzo Highsmith’s, or any of those great players homes and I would go in and they would sit around and tell me they were going to take care of my car to make sure no one stole my car” (Schnellenberger, 13 April 2015).

By entering those neighborhoods, neighborhoods that even the police feared going into at the time, much less driving a car the color of his skin, Schnellenberger was breaking down racial barriers at exactly the right time that his approach was needed. As was stated in the ESPN 30 for 30: The U documentary, “Schnellenberger strengthened ties between the school and the city by recruiting players from Miami’s ghettos and ethnic neighborhoods” (Cohen, Alfred. ESPN 30 for 30: The U).

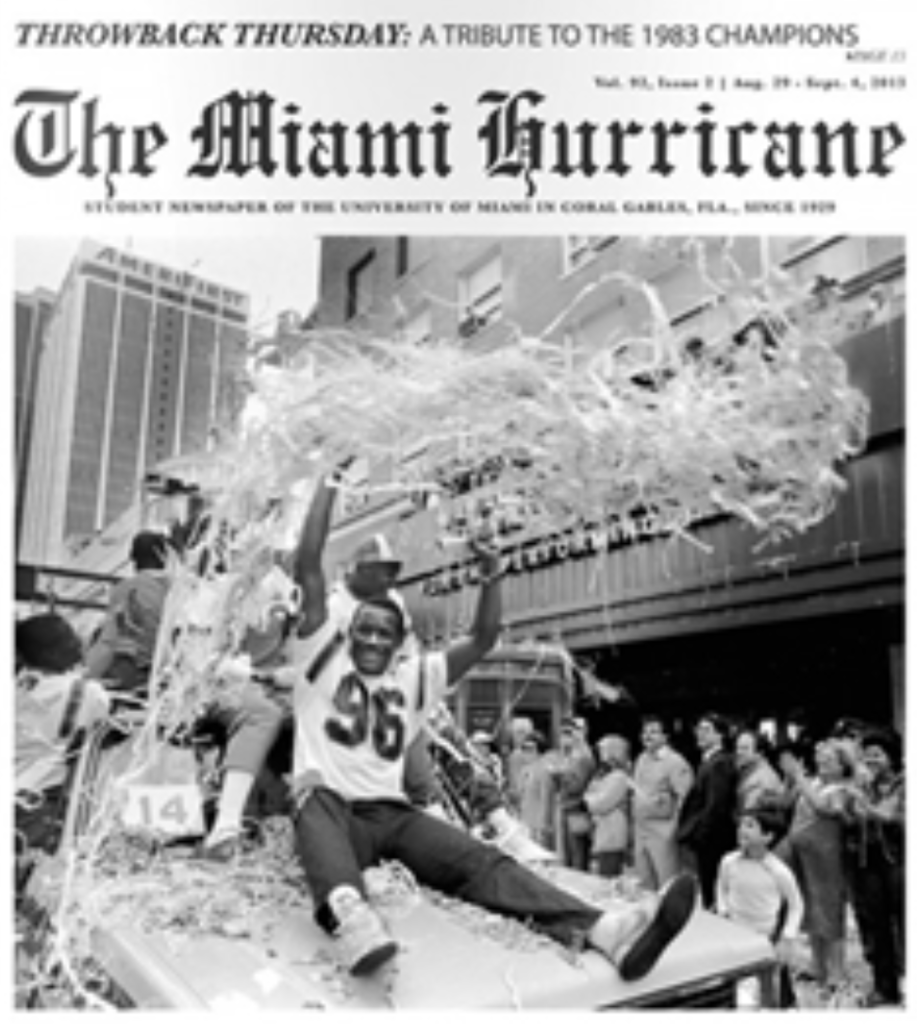

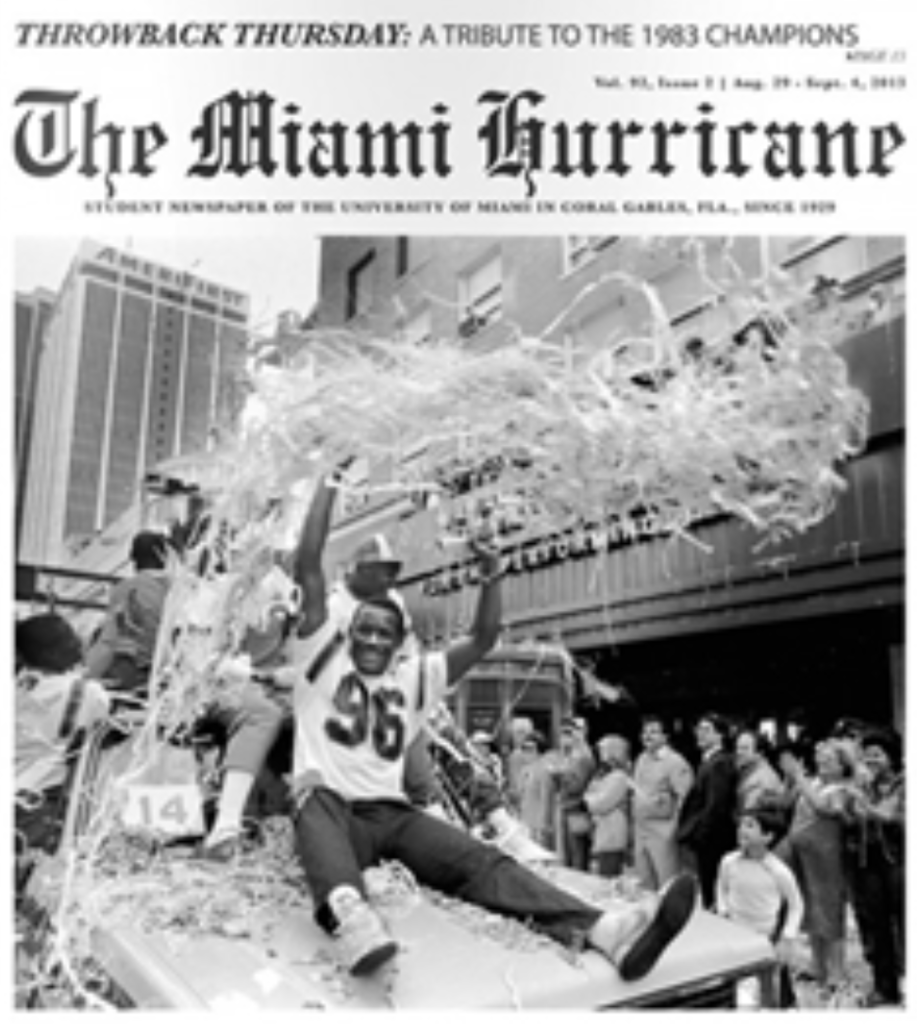

Article on a tribute to the Hurricanes’ big championship win

Article on a tribute to the Hurricanes’ big championship win

Along the way his team quickly came to look like the multicultural community that Miami had become. And yet, as riots raged just a few miles away, the school and team were safe harbors to its players no matter the color of their skin or where they were born. The locker room, in fact, was an oasis where players treated each other as “blood brothers,” according to Schnellenberger. As coach explained to me, his team, which was becoming the most successful in the country, did so because of the mutual admiration that each player had for one another without regards to their backgrounds, where they were born, nor their race. His approach allowed his teams and the school to become a beacon of what was possible, of how people with all sorts of differences could come together, work together, live together, and do so peacefully and happily (Schnellenberger, 13 April 2015). In fact the film about the University’s football program from ESPN stated, “For now, it doesn’t matter what kind of accent you speak with or where you come from, around Miami, college football has brought everybody together” (Cohen, Alfred. ESPN 30 for 30: The U).

It wasn’t always like this though, nor was it easy for the coach, the school, or the community. As noted, racial tensions in South Florida in the late 1970s and early 1980s had grown to epic proportions. Schnellenberger explained, “It took a gigantic effort from religious people, politicians, and leaders of the community to work it [the riots and their aftermath] out and get it straightened out so that we live in a peaceful climate now in Miami, Broward, and Palm Beach Counties” (Schnellenberger, 13 April 2015). Schnellenberger, his diverse football team, and the school had a big role in this “new and improved” Miami.

One of the many steps they took included starting an organization entitled Hit the Books and Get the Grades. The program invited football players to all of the high schools and middle schools in the Miami area to help students improve their grades to stay in school and graduate. The program even had contests in which the children who raised at least two of their grades by a letter grade would qualify for a big pep rally at the end of their school year. Schnellenberger said, “The Miami community was very big on public awareness and was publically concerned in the willingness to work and to give money so that we could have the best of things for all our citizens” (Schnellenberger, 13 April 2015). These programs, Coach Schnellenberger and his team, as well as the community seamlessly worked to ease the pain and prejudice that had been boiling under South Florida for decades. “They made a city forget a drumbeat of bad headlines and newspapers, racial strife, riots, drug wars, and crime.” (Cohen, Alfred. ESPN 30 for 30: The U).

Segregated seating in the Florida Orange Bowl Stadium in 1955

Howard Schnellenberger and his seemingly bold predictions about wanting to bring a national championship to a school that, just a few years earlier, had nearly ended its football program gave people hope. In his trademark coat and tie, along with his ever present pipe, the coach destroyed barriers and calmed people’s fears at a time that they needed it the very most. The days of people sitting in segregated seating or being forced to enter a building through a door based on their color had ended and, as they watched his diverse team’s happiness and national success, people began to accept the fact that other races and cultures were here to stay in this beautiful fusion we call Miami. Watching those young men play a game with one another, knowing that their leader, Coach Schnellenberger, was often in their own community without fear, helped end the fright that had been rampant just a few years earlier. According to Schnellenberger, “We were in hell at the time of the riots and all of those things, today we’re in paradise, as it relates to race relations” (Schnellenberger, 13 April 2015).

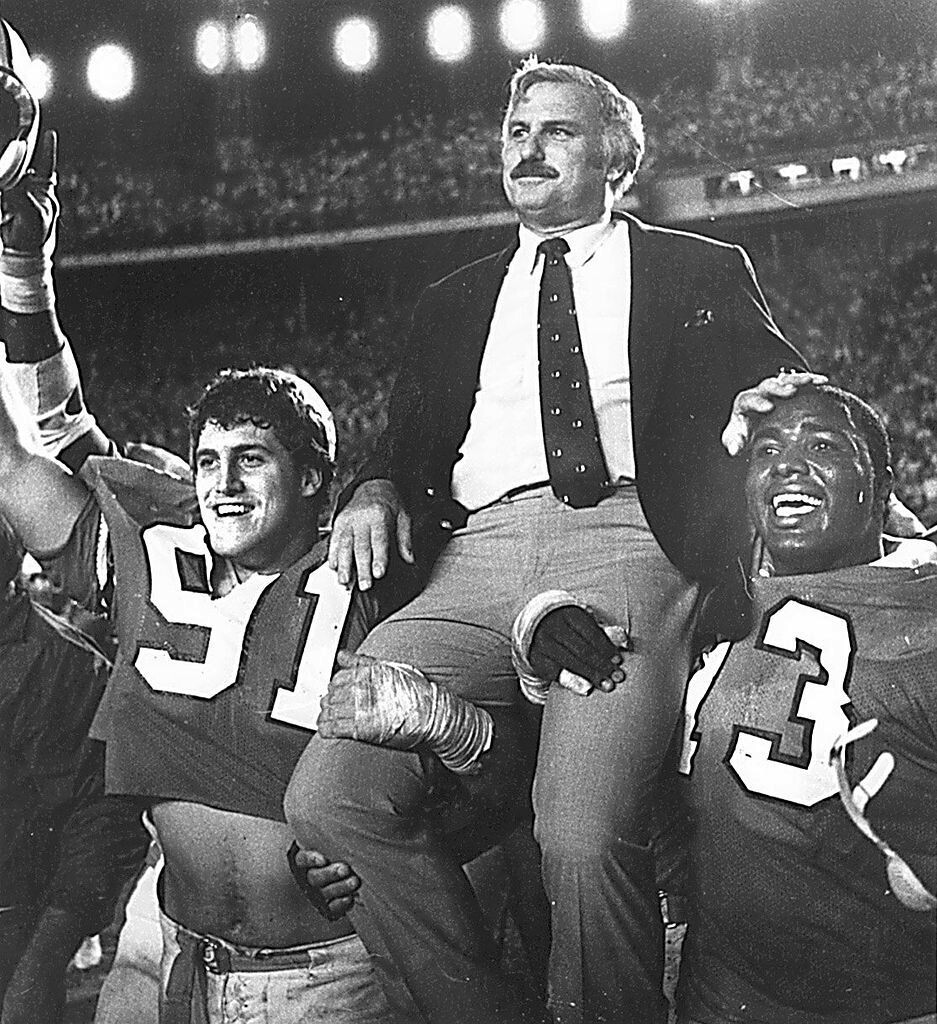

While Schnellenberger is well known for his work in football and on the field, he is, at his core, an innovative educator. Along the way to building the University of Miami football team into a National Champion, a title the school first won in 1983 under his guidance, he helped cure a community and calm a nation filled with questions about how diverse people could coexist. His recruiting style and the way he viewed and treated his players on and off the field had one of the biggest impacts on the history of not only our city, nor state, but eventually our nation. As the result of Schnellenberger’s efforts to promote equality within the community of Miami through his coaching, race relations eased, the mentality of egalitarianism to races has spread like wildfire, and have improved more and more each year since the beginning of his “reign” here in Florida. As proud as that title was to the school, coach, and players, it was and remains the positive impact that Coach Schnellenberger had on calming our city at a time that it was literally on fire that should be his legacy. Far more important than any football game or title was the example his teams set for all of us to see, to witness that a group of people of different colors and backgrounds could find success and peace and love for and from one another. The unity that Coach Schnellenberger bestowed on our community and country was easily his most important “national” championship.

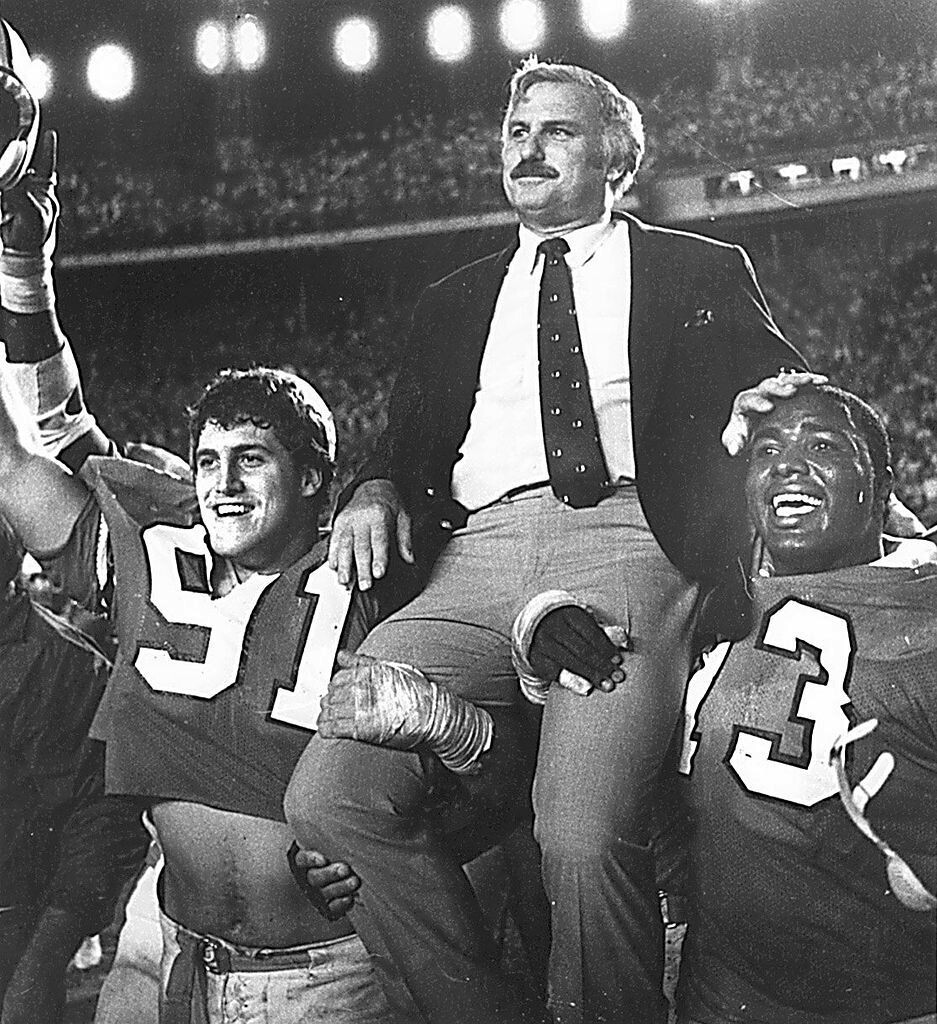

Howard Schnellenberger with players after winning the Orange Bowl in 1983