Are Natural History Films Really Raising Environmental Awareness?

The following article first appeared on the Research Blog for Dr. Neil Hammerschlag’s Shark Research and Conservation (SRC) Lab website at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. To learn more about SRC, visit here: http://sharkresearch.rsmas.miami.edu/, or to learn more about the University’s marine science school, please click here: http://rsmas.miami.edu/.

By: Delaney Reynolds, SRC intern.

Films have influenced the way people perceive certain topics for decades. We all know and love the Jaws theme song, but soon after the movie’s release, mass hysteria broke out and a negative stigma has been associated with sharks ever since. Here at Shark Research and Conservation we, of course, know these apex predators are nothing to fear, but rather a respectable species that can provide us with a lot of information regarding environmental vitality. Thankfully, many others recognize this as well and social media platforms have played a very large role in dissipating the adverse reputation sharks have obtained. With social media ruling the world we live in today, are natural films and documentaries doing as well of a job at educating about conservation issues? Researchers at the University College Cork and University College Dublin set to find out.

In 2016 the British Broadcasting Company (BBC) aired its wildly popular show Planet Earth 2 narrated by Sir David Attenborough. The show brought in over 12 million viewers (BBC News). By looking at the engagement on Twitter and Wikipedia between November 6th to December 11th, 2016 (when the show aired), a qualitative analysis was performed based on the show’s script, the animal species it mentioned, the screen time they each were given, and conservation themes. In total, 113 animal species were mentioned and classified as mammal, bird, reptile, amphibian, fish, and invertebrate (Fernandez-Bellon, Kane, 2019). It was also noted that each species was described in part based on their predator-prey interaction.

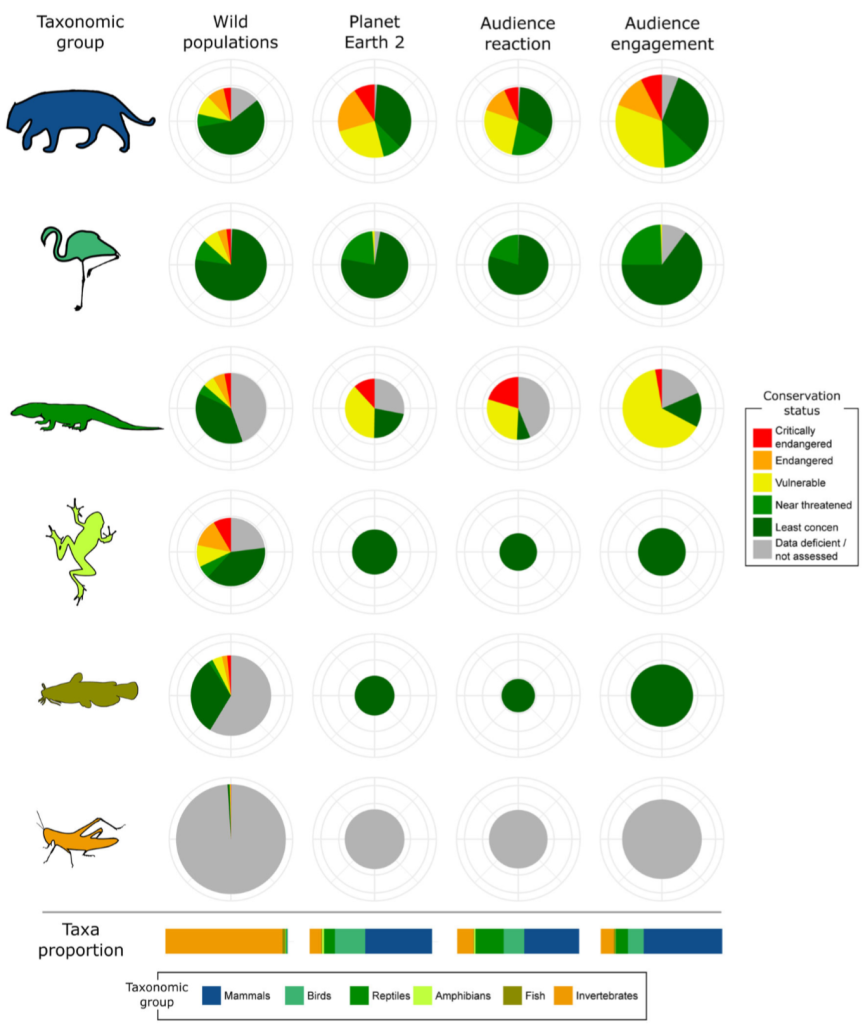

Figure 1: The proportion of taxonomic groups based on screen time and IUCN conservation status. The number of species is represented by circle size, colors represent the IUCN conservation categories, bars represent taxonomic groups and proportions, and changes in circle size represents differences in screen time (Source: Fernández‐Bellon et al. 2019).

Based on the qualitative analysis, it was found that mammals were overrepresented in the show, thus all other categories were underrepresented, and the screen time that was allocated to specific species based upon their IUCN categories did not discuss or reflect conservation priorities (Figure 1). As such, audience engagement was highest in response to the mammals on the show and animals with an IUCN “least concern” conservation status also dominated airtime.

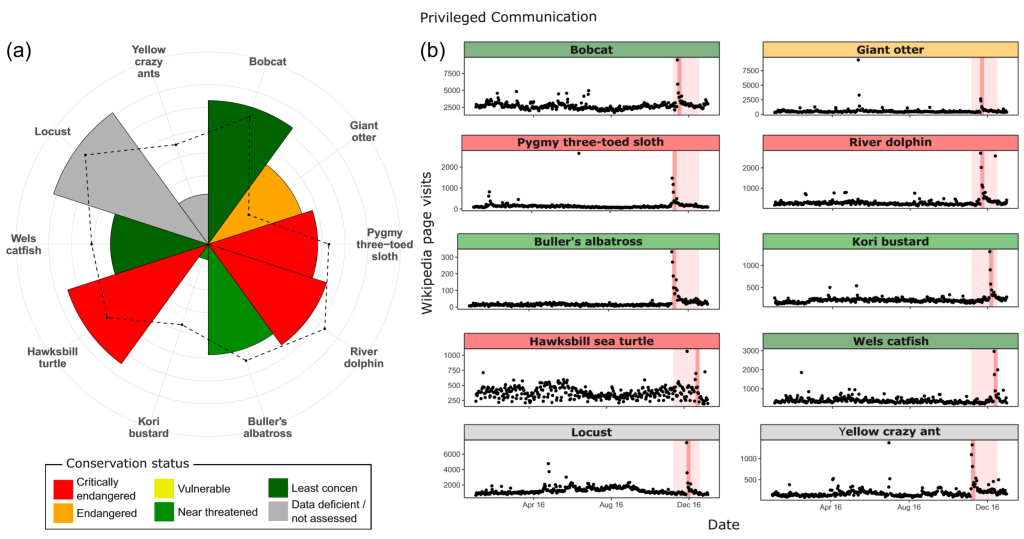

Figure 2: Audience engagement for ten species that were featured in Planet Earth 2 from (a) Twitter and (b) Wikipedia. Twitter engagement was based on the number of times each species was mentioned under #PlanetEarth2 and Wikipedia engagement was based on the number of visits to each species’ specific page. Colors represent the IUCN conservation status, red shading in (b) represents the 6 weeks that Planet Earth 2 was aired, and the darker red band illustrates the specific episode each animal was highlighted in (Source: Fernández‐Bellon et al. 2019).

In total, 30,000 tweets were posted under #PlanetEarth2 during the broadcast of the show and it was evident that species screen time per episode had a significant impact on audience engagement. Only 6% of the entire script for the show was dedicated to conservation education, leading to 1% of tweets mentioned containing conservation themes (Figure 2a). Based on the Wikipedia analysis, 41% of the animal species highlighted in the show recorded a yearly peak in page visits during the episodes of their respective animal species and, again, screen time of animal species had a significant effect on engagement (Fernandez-Bellon, Kane, 2019). The more screen time an animal received, the more it was tweeted about or searched for.

Given the extreme success of nature films and documentaries, just like Planet Earth 2, they can be fantastic platforms to educate a large amount of people about different conservation and environmental issues. Unfortunately, Planet Earth 2 did not feature conservation themes nearly enough, but this study shows just how effective such a platform can be in informing an extensive audience and with environmental issues emerging as a key issue for our society, it will be crucial to include them. So, no, not all nature films are currently doing their job in raising environmental awareness

Works Cited:

Fernández‐Bellon, D, Kane, A. Natural history films raise species awareness—A big data approach. Conservation Letters. 2019;e12678. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12678

“Planet Earth II More Popular than X Factor with Young Viewers.” BBC News, BBC, 1 Dec. 2016, www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-38170406.