Math & Science

My brother Owen has always been a bit of a math whizz and just loves numbers. He’s also an incredibly creative guy and his comfort with math serves him well as a student at the world’s top ranked architecture school. Me? While I’ve taken all sorts of advanced math courses over the years through high school and college, my passion has always been science. Find me on the back of a boat catching sharks to perform scientific studies before releasing them back into the wild and I am happy as a hermit crab who just found a new shell to call home after outgrowing its last. I find this dichotomy between us a bit amusing because I’ve been so deeply immersed in math as part of my research at the United Nation’s COP meetings as I study ways for the world to finance the solutions society needs to solve our climate crisis.

You’ve heard the old saying “follow the money.” Well, the transition to our sustainable energy economy is driven by environmental need, given how earth’s warming from fossil fuel use is impacting our atmosphere and oceans, but it’s also about money, namely the economics of how the world will pay for this incredibly complex transition. For this reason, the UN’s climate meetings focus on what the science tells us is happening, but a significant part of the discussion relates to numbers. Lots of numbers. Especially the money needed to make the transition a reality, including adaptation and resiliency.

With the first week of COP28 here in Dubai having ended, it’s a good time to reflect on one of the early successes given the prospects it holds to help many people around the world and because it illustrates how agreements amongst the world’s nations at these meetings tend to evolve over time. The subjects, solutions, and implementation costs are some of the most complicated and expensive issues of our time. And for that reason, it’s understandable that progress often takes time as the nations of the world research, debate, and negotiate solutions – along with financing – to make them a reality. In some cases, that’s years. In others, its decades.

Last year in Egypt during COP27 I spent a great deal of time learning about what the United Nations calls a “Loss and Damage Fund” (you can learn more from my post “Life Over Death” here), created to specifically address the impacts of the climate crisis on physical and social infrastructure in poorer countries so as to finance things like adaptation and resiliency projects. A key element of those negotiations was to create a dedicated financing mechanism to help lower income countries, vulnerable nations that disproportionately suffer the impact of our climate crisis but have done little-to-nothing to cause the pollution (like the Republic of Seychelles mentioned in my post in 2022), to provide them a sense of climate justice security.

As I sat in one meeting after another on the subject it was clear that many in attendance worried about whether an agreement could be finalized in Egypt on a topic that’s been discussed at UN climate meetings since 1992. Many of the impacted nations made dire pleas for help as their way of life and places they have lived in for generations are threatened despite not having causing the problem. Ultimately an initial agreement, imperfect in the view of many, was reached 36 hours after the Conference’s scheduled end and touted as a signature success of COP27.

Here in Dubai the good news from the first week of COP28 is that a handful of countries have agreed to provide very initial funding for the Loss and Damage Fund that actually, theoretically, makes the Fund operational. As of this blog post, about $700 million USD has initially been committed including $100 million from COP28 host country the UAE, $100 million from Germany, $108 million each from France and Italy, $50 million from Denmark, $27 million each from Ireland and the EU, $25 million from Norway, $17.5 million from the United States, $11 million from Canada, $10 million from Japan, and $1.5 million from Slovenia as a few examples.

While that sounds like a great deal of money, the reality is that it’s just a fraction of what’s needed (less than 0.2% by some estimates) to address the impact from our climate crisis on developing nations, a figure experts estimate to range from $100 to $400 billion per year. Many questions about the Fund remain unanswered including when and how the money can be deployed, how (or if) member nations will plan the exponential increased needed year over year to actually address the projected costs, or why one of the world’s largest polluters (sadly, the United States) contributed such a relatively (some rightfully say embarrassingly) small amount, all remain. But, the funding announcement is at least a start and, thus, that’s good news.

And speaking of UN climate finance and COP28, allow me to share an article I wrote that my University, the University of Miami, just published about topics that I am researching here in Dubai, the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and Green Climate Fund (GCF), as well as the presentation itself. The article relates to a presentation that I had the profound honor of making here in Dubai to my School of Law colleagues, esteemed professors including Dr. Jessica Owley, our Executive Director Michael Berkowitz of the University of Miami’s newly established Climate Resilience Academy, and others. Here’s the published summary:

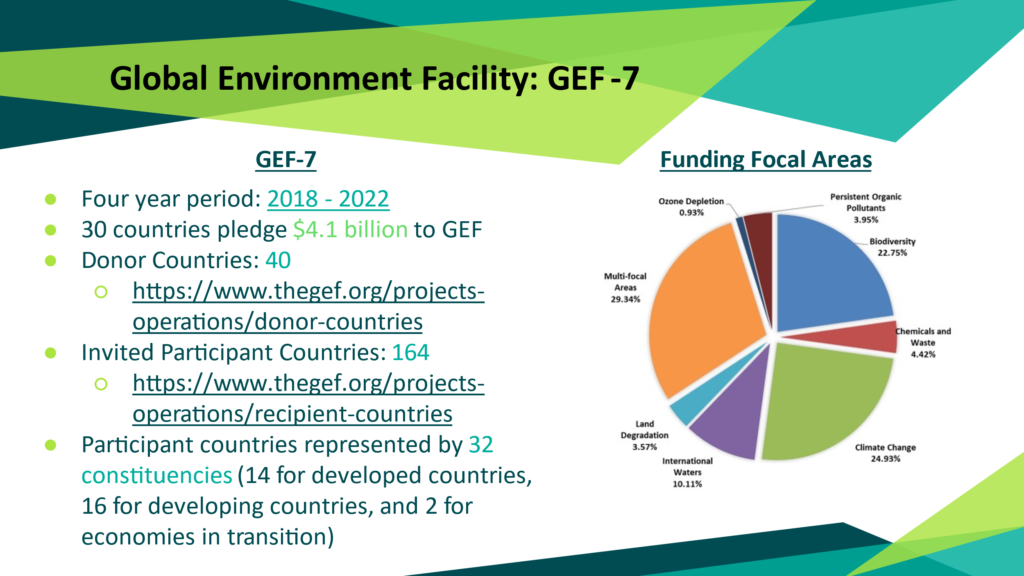

The idea of the Global Environment Facility, yet another funding tool organized by the United Nations for both developed and developing countries focuses on environmental conservation, protection and renewal for biodiversity loss, climate change, pollution and strains to land, and the health of oceans. Here’s a slide from my talk that details the numbers of GEF funding from 2018-2022:

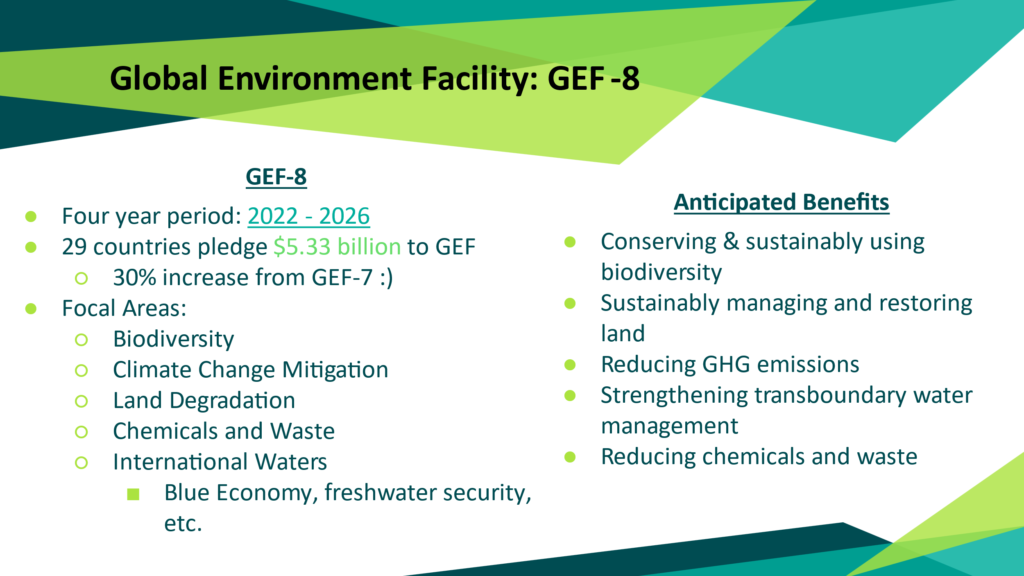

Over the past three decades the GEF has provided $23 billion USD in direct funding and another $129 billion in co-financing to address over 5,000 projects all over the world. And the projected benefit from the GEF, now in its 8th iteration, is expected to grow as outlined in the following illustration, also from my recent presentation:

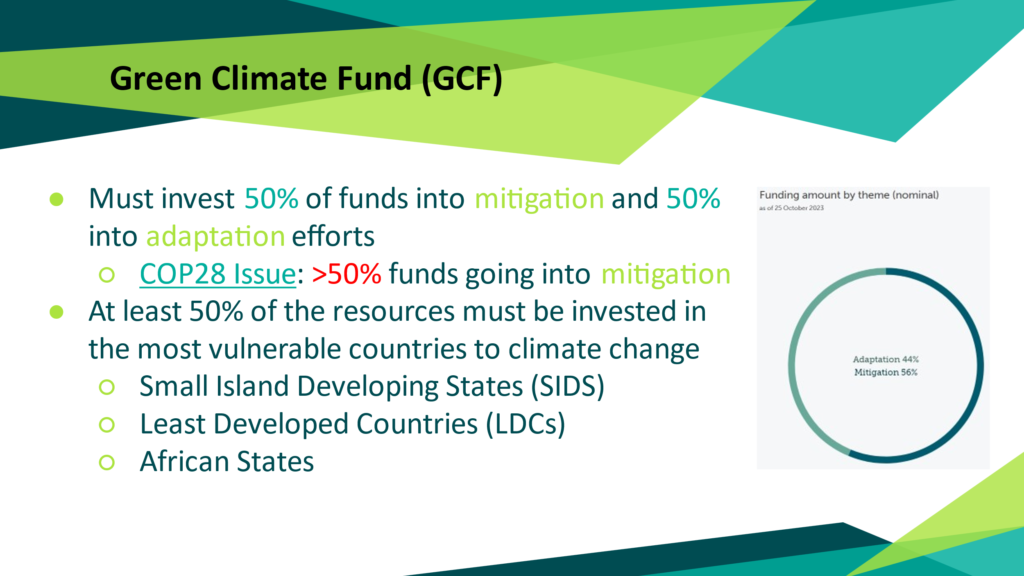

During my presentation we also discussed the UN’s Green Climate Fund program, the world’s largest climate focused fund designed to support developing nations by helping raise their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs: steps they can take to reduce greenhouse gas pollution and implement resiliency measures to adapt to the impacts of climate change).

These funds are focused on four transitional topics: the built environment, energy/industry, human security/livelihoods/well-being, and land use/forests/ecosystems. Approved projects require that half (50%) of the allocated funds are invested into mitigation and half (50%) in adaptation with a focus on Small Island Developing States (SIDS), Least Developed Countries (LDCs), and African States.

The 243 (and counting) GCF projects are having a major impact all over the world by helping an estimated one billion people be more resilient while avoiding an estimated three billion tons of carbon dioxide from reaching our atmosphere and oceans.

Hopefully the financial topics I’ve mentioned in today’s post give you a sense of the work taking place by the United Nations during these Conferences, much less all year long. That work truly never ends. And with that in mind I’m off to attend meetings on the Global Stocktake, the first true worldwide accounting (speaking of math) of society’s “progress” towards reaching the goals that the nations of the world agreed to in the Paris Agreement at COP21 in 2015.

The Global Stocktake report will be the most important story of COP28 and our time here in Dubai. The report will be filled with a ton of critically important science (yay!) and, yes, a whole lot of numbers and math that collectively will show the world whether our society is actually making progress in its fight to fix our warming climate, along with a roadmap for the extensive work that remains ahead of all of us.

Will the nations of the world take that story, the science and math within the Global Stocktake report, seriously? Does mankind have the fortitude to significantly adjust our ways, to take the aggressive, often difficult steps that will be necessary to meet the milestones agreed to in Paris to transition to our sustainable energy future and to mitigate the worst impacts of the climate crisis?

Or will the nations and businesses around the world that profit from producing the fossil fuels that are warming our atmosphere and oceans succeed in perpetuating their polluting ways?

How the world responds to the forthcoming report, to the math and science within it, will define our future.